Back in February I found myself with a full day free. With the regular rains this Winter I hadn’t gotten much hiking in. It was a cool day with light cloud cover, good weather for a hike, and so I decided to head out and see an old friend.

Along the eastern edge of the San Fernando Valley, where La Tuna Canyon Boulevard meets the 210 freeway, is an old road winding up a rugged slope of chaparral. I used to live nearby and the road made for a nice after-work hike to clear the mind. That was ten years ago. Tired of the long commutes, my wife, newborn son, and I moved out of the Valley to the western side of Los Angeles. But not the Westside, more of just east of the Westside. I hadn’t walked up that old road since.

The road is gated off, used occasionally by trucks coming to service the power lines or the radio towers. The first half mile is a wide, cracked track of asphalt, perhaps a continuation of La Tuna Canyon Blvd before the 210 Interstate was pushed through this region.

Though cracked, the road is in fairly decent shape. Still, at the edges, nature is slowly chipping away at it, seeking to reclaim old territory. In one crack some years ago, a mulefat seed took root. The mulefat (Baccharis salicifolia) has managed to get itself established, each year expanding more and widening the crack.

I wasn’t sure what I was going to find. In 2017 a major wildfire burned in this area. Driving up La Tuna Canyon, charred slopes are on both sides. Reminders of the fire were everywhere from barren hillsides to a burnt stick laying among the grass. Over seven thousand acres of brush were burnt. Would anything I remember still be around? Relief came when I saw most of the canyon side that the old road traversed was mostly spared, though another trail I had driven past was devastated.

After a short climb, the paved section ends and a narrow dirt road breaks off from it. Looking back, the 210 can be seen running through the area but the rest of the view is hillsides – some charred, others with a thick coat of chaparral. Rarely having heavy traffic, I liked driving this stretch of the 210. For a couple of miles there was no sign of the city. If there wasn’t ten lanes, it could have been an empty stretch of a cross country byway.

Like most natural areas around Los Angeles, non-native grasses line the trail, but the flora here is mostly native plants. This is a rare spot where the invasive grasses were shoved aside by California sagebrush and California buckwheat. A healthy patch of chaparral, this vibrant ecosystem left little room for invasive plants to get a foothold.

The dirt road climbs up the backside of the Verdugo Mountains. This little mountain range, only eight miles long, rises to over 3000 feet, standing two thousand feet above the San Fernando Valley. The mountains are surrounded by the cities of Burbank and Glendale along with the Los Angeles communities of Sun Valley, Sunland, and Tujunga. The Verdugos sit in the shadows of the taller San Gabriel Mountains. Despite being surrounded by an urban landscape these mountains preserve an example of what many hillsides in Los Angeles once looked like.

When I regularly hiked this area, my interest in native plants was just starting to get piqued. Most plants I wandered by I did not recognize. A few I could name, but most were a mystery to me. Hiking along this road now was like unlocking a puzzle. Each plant I am able to identify is a key to unlocking this ecosystem and seeing the connections within it and to other regions. The sugarbush (Rhus ovata) with its tiny red flower buds is a close cousin to the lemonadeberry (Rhus integrifolia) found in the hills near my home. With a more mild coastal climate, the lemonadeberry has been flowering since January. Here on colder north facing slopes of the Verdugos, the sugar bush is still waiting for Spring warmth to bloom.

Some California natives though are down right creepy. Dodder (Cuscuta sp.) is a strange, orange parasitic plant found in the chaparral, twisting and twining onto its host plant. Lacking leaves and the green chlorophyll that turns light into food, dodder takes it nourishment from the host plant. With the heavy rains this year, the California buckwheat (Eriogonum fasciculatum) might be able to survive this dotter infestation, at least this year, but in a drought year the buckwheat maybe overwhelmed and not survive this parasite.

At the edge of the road is a Our Lord’s Candle (Yucca whipplei) , a yucca. Grateful for the extra width provided by the road for the leaves are tipped with very sharp points. Upon maturity, around seven years, a tall stalk will grow out of the center, up to ten feet high. By late Spring, the hillsides are spotted with clusters of white flowers blooming at the top of the stalk. Hence the name – Our Lord’s Candle. While beautiful, they are also a last hurrah. After flowering, the yucca will die. At the base of the dying plant though are usually several pups to start the cycle over.

The clouds grew thicker as I continued hiking, the gray light muting the green of the hillsides, giving them a drab appearance. But grayness only made the new leaves on the laurel sumac (Malosma laurina) appear bolder. Many plants’ new leaves first unfurl in colors of yellow to orange to red. Few though are as intense as the laurel sumac, whose new leaves are a deep saturated burgundy red. Maturing, they’ll turn green with the midrib and the edges retaining the red coloring well into summer time.

But why red? There’s a couple of ideas I’ve heard tossed around. New leaves are very tender and more prone to damage. One idea is the yellow and reds of the new leaves provide protection from the ultra-violet rays of the sun. Another idea is because new leaves are more palatable than older leaves, so they are more attractive to herbivore insects. But leaf-eating bugs’ eyes are better tuned to green than red and yellow. So the emerging colored leaves are harder to see and insects are less likely to eat them.

Now this was unexpected. What once was the dirt road is now a fifteen foot deep ravine nearly twenty feet across.

Further up the road was a ravine with a seasonal stream that often runs into the summer. A metal culvert buried under the road allows the water to cross. But the culvert isn’t well maintained, its entrance usually half blocked by dirt and rock debris.

The Verdugos are steep. Once water starts flowing down, it goes fast. The runoff from the latest storms turned the stream into a torrent bringing enough debris down to block the culvert. And rivers being rivers, the water just cut itself a new path in the road.

Notice though the length of the roots exposed by the wash out. Their length shows one of the ways chaparral plants survive in a region that can go nine months between rains, tapping moisture deep in the ground.

The rushing water also reveals the rocky bones of the mountains. The wavy layers and cracks in the stone are testament to the forces this region is subjected to where continental plates collide and mountains are pushed up.

Luckily a rock ledge remained, allowing me to get past the ravine. Of course, not everyone was so lucky. I don’t know how long this car has been here but I always made sure to check it out whenever I hiked past it. What was the story – a ‘James Dean’ moment when a teen lost control racing on the dirt road? A crime scene perhaps? Or, maybe, just plain bad luck.

Although the mountain side is dominated by shrubs and brushes, several species of trees grow here too, mostly along the edges of the ravines that channel the rain runoff down the slope. California bay (Umbellularia californica) is one of those trees, seen here with flower buds forming on the end of the branches. A distant relative of its culinary cousin, sweet bay laurel, I’ve heard one source say these leaves cannot be used for cooking, another saying they can but only use a small pinch of the leaf. Culinary daredevils out there proceed with caution.

Another plant related to a common kitchen herb is black sage (Salvia mellifera) which supposedly can be used for cooking. While one of the most common of the California sages, its smaller, paler flowers tends to let it be eclipsed by more showy cousins such as purple sage and Cleveland sage. But it’s still an attractive plant with a wonderful aroma. These two young sprouts cling to an exposed slope by the dirt road, along with some blooming California morning glory.

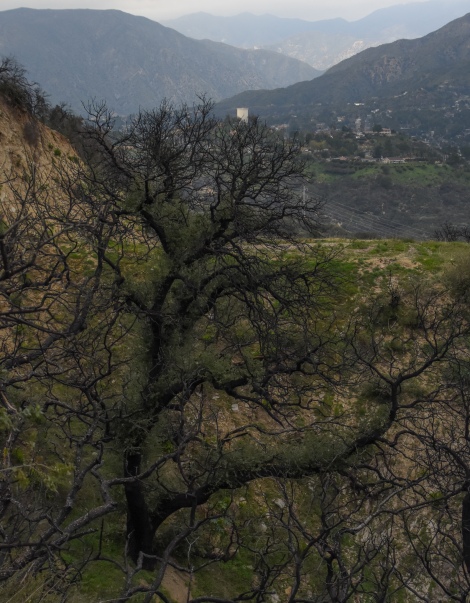

Unfortunately, this area wasn’t completely spared by the La Tuna Canyon fire. Haunting skeletal remains of large shrubs and trees marked the fire’s edge. Though burnt and charred, there is a certain dignity and beauty remaining in the branches.

One plant I was surprised to come upon was manzanita (Arctostaphylos sp.). Even though I was just learning about native plants when I regularly hiked here, I had known about manzanitas with their tough olive green leaves and smooth red bark. They are a signature California native. Yet I didn’t think any lived along this trail till this hike. Manzanitas tend to bloom early in the year so by the time of this hike most of the flowers were gone. The flowers are tiny and delicate upside-down urns.

There are a large number of manzanita species in California, some forming dense ground cover, others, like the ones here, growing into small trees. The tall manzanitas here are likely big berry manzanitas (Arctostaphylos glauca). I noticed many of the manzanitas had patches of red dead leaves. Last year was one of the driest years on record. The dead leaves may be the scars from that drought.

Of course, I can’t talk about manzanitas without at least one picture of their trunk and bark. If you ever get a chance, run your fingers along the bark. It’s smooth to the touch as if the rough edges were carefully polished off. It is the most defining and striking feature of manzanitas, so why I didn’t recognize this before I cannot say.

Another common plant found along the trail is chamise (Adenostoma fasciculatum). This is an extremely tough drought tolerant plant. In adapting to the hot dry summers and periodic droughts found in California, its leaves have shrunk, resembling tiny little pine needles. The smaller leaves means less moisture lost to evaporation.

Like manzanita, chamise is a slow growing, long living plant as seen from the gnarled lichen-covered trunk. Chamise grows into a large brush or small tree up to twenty feet high.

Another plant with delicate small flowers is chaparral currant (Ribes malvaceum). It is interesting that while some plants can dominate an area as the manzanita and chamise do, others seem to live in isolation. I saw no other currants along the the trail, just this one growing underneath two larger plants.

Eventually the top of the mountains come into view, marked with radio towers. It is hard to believe on the other side of this ridge live millions of people.

I came upon some California everlasting (Gnaphalium californicum) , a white flower that is more attractive as a bud. Here they look refined and delicate, but the bloomed flower looks a bit scraggly. The flower goes by many other common names: lady’s tobacco, rabbit tobacco, and the very unappealing name of cudweed. I always associate this flower with my grandmother Genevieve. Not sure why, but buds look like something I would see in vase arrangements in her home.

Here is white sage (Salvia apiana) , a favorite for gardening with California natives. Hard to imagine looking at this one. It is interesting how some native plants look so good in the garden but can appear a bit ratty in nature. Though drought tolerant, the sage in the garden receives extra water during dry years. On it own, it may go years surviving on less than ten inches of rain a year with none during the hot summer. Springtime flower stalks grow up to six feet tall with white flowers up and down it. Once done blooming, the flower stalks die off. In the garden, trim those stalks back, leaving a nice compact plant. But with no one to trim, the stalks remain on the plant for years.

This fellow took me a while to ID. At first I thought it might be a type of ceanothus but the flower clusters didn’t look right. Ceanothus flower clusters tend to be elongated, like a cluster of lilac flowers (hence one of ceanothus’ common name, California lilac). But these flower clusters were rounder and flatter. Holly-leaf cherry? Nah…

The leaves were small and leathery with serrated edges making me think maybe scrub oak, but oaks don’t flower like this. Birch leaf mountain mahogany? The leaves are the right shape and size, but they don’t have serrated edges.

Back home on the web, referencing Calflora and comparing photos, I got confirmation that one’s first instinct is usually the right one. Ceanothus. Hoary ceanothus (Ceanothus crassifolius) to be exact.

Like manzanita, ceanothus is found through out California and make up dozen of species ranging from small ground cover to large bushes twenty feet high. Hoary ceanothus is a mid-size one and like most ceanothus blooms in late Winter or early Spring.

Approaching the top, I enter into the La Tuna Canyon fire area. In some places new growth was coming back, other areas are still barren, just burnt branches and bare ground. A lot of people think the chaparral is adapted to fire with an implication that it is almost meant to burn. That is not true.

Like an old growth forest, the chaparral goes through a succession of stages starting with pioneering plants and wildflowers which provide shade for the seedlings of longer lasting plants. Soon the pioneer plants are shaded out with the new plants, which themselves may eventually be replaced by another succession of plants. The manzanita and chamise I’ve passed on the way up are slow growing plants with a long life. They need decades without fire to reach full size. If fire comes too regularly, they’ll never be able to get reestablished.

At the top of the ridge I saw that the fire had crossed onto the other side. A year before I moved from this area this side had suffered a wildfire. And now, ten years later, another fire. Bushes getting established were burnt down. With each fire that comes through, the area is more vulnerable to invasive grasses, mustards and other non-natives.

Still, the adaptions the chaparral plants evolved in response to fire are amazing. Seemily dead laurel sumac have new growth sprouting from its base.

In an area of dead oak trees, a coastal live oak (Quercus agrifolia var. agrifolia) appeared to have a green fuzz growing on it.

Hiking closer to it, a frenzy of new branches sprout from the trunk and major branches. It may never be as healthy as it was before the fire, but may last long enough and produce enough acorns to start the next generation. Life goes on.

By now the views are amazing. I can look out over the San Fernando Valley to the Hollywood Hills and the high rises of Century City. The glow on the horizon is the Pacific Ocean reflecting the light of the sun.

Behind me I see the higher and rugged San Gabriel Mountains. Storm clouds were gathering and swirled around their peaks.

When I left my home this morning, the weather report showed little chance of rain for the day. But the clouds said differently. It was cold at the top, much colder than I expected. By now I was on the high peak with no shelter from the wind. Man, I wished I packed some gloves. By the time I started back down a light drizzle began. Later that day, snow will fall in parts of Los Angeles for the first time in decades. The top of the Verdugos get snow maybe once a year so I’m sure they did that day.

Before heading back down, I took in the view again. From my perch I looked past downtown Los Angeles. Thirty miles away I could see the big loading cranes that line the Ports of Long Beach and Los Angeles, and further beyond, the frieghters waiting to dock.

Yet the best views were smaller. A few flowers on a California buckwheat – completely out of season. I couldn’t say if it was an extremely late bloom or extremely early. But it was a magical as any vista.

Photographs by Alan Starbuck

Another interesting column. Good work.

LikeLike

Thanks!

LikeLike

Fascinating article. Loved following your observations on you walk I felt as if I was walking along with you. Thanks for the hike.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks!

LikeLike

How compelling. There is so much of Southern Californian I have never seen. I don’t think people realize how different each of the mountain ranges there are. We have mountains too, but they are more predictable, with the Santa Cruz Mountains on one side, and the Diablo Ranges on the other. They are very different from each other, but there is either this or that. I still can not remember all the ranges around the Los Angeles Region.

Nor do I remember which variety of Yucca whipplei grows where. My favorite is the familiar one in San Luis Obispo, but there are either two or three others in your region. The fourth is in Baja Mexico.

LikeLike